Science & Technology - Planetary System

Study of the solar system

- The solar system took shape 4.57 billion years ago, when it condensed within a large cloud of gas and dust.

- Gravitational attraction holds the planets in their elliptical orbits around the Sun. In addition to Earth, five major planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) have been known from ancient times.

- Since then only two more have been discovered: Uranus by accident in 1781 and Neptune in 1846 after a deliberate search following a theoretical prediction based on observed irregularities in the orbit of Uranus.

- Pluto, discovered in 1930 after a search for a planet predicted to lie beyond Neptune, was considered a major planet until 2006, when it was redesignated a dwarf planet by the International Astronomical Union.

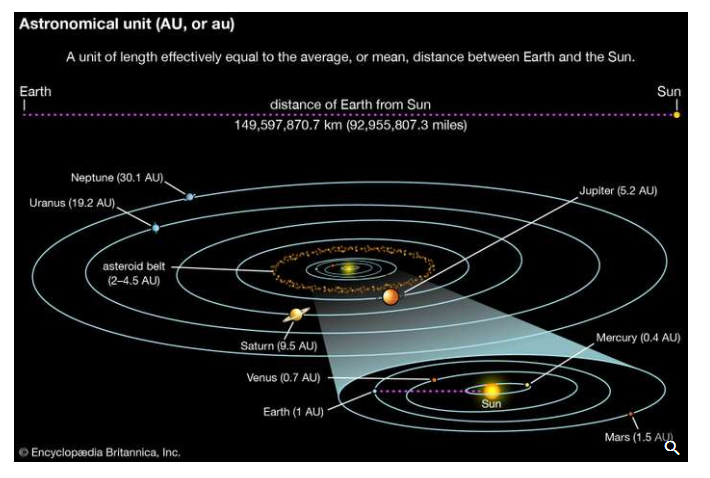

- The average Earth-Sun distance, which originally defined the astronomical unit (AU), provides a convenient measure for distances within the solar system.

- The astronomical unit was originally defined by observations of the mean radius of Earth’s orbit but is now defined as 149,597,870.7 km (about 93 million miles).

- Mercury, at 0.4 AU, is the closest planet to the Sun, while Neptune, at 30.1 AU, is the farthest.

- Pluto’s orbit, with a mean radius of 39.5 AU, is sufficiently eccentric that at times it is closer to the Sun than is Neptune.

- The planes of the planetary orbits are all within a few degrees of the ecliptic, the plane that contains Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

- As viewed from far above Earth’s North Pole, all planets move in the same (counterclockwise) direction in their orbits.

- Most of the mass of the solar system is concentrated in the Sun, with its 1.99 × 1033 grams.

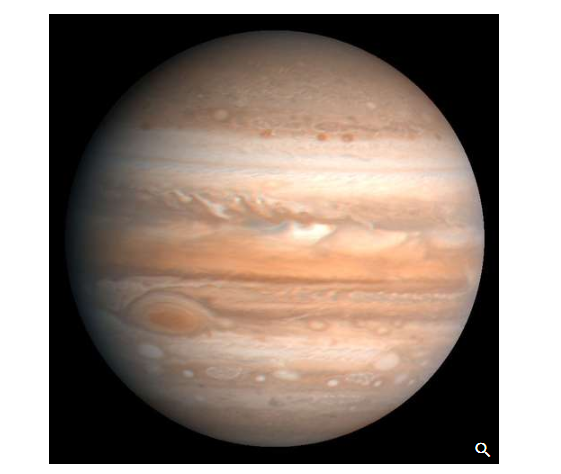

- Together, all of the planets amount to 2.7 × 1030 grams (i.e., about one-thousandth of the Sun’s mass), and Jupiter alone accounts for 71 percent of this amount.

- The solar system also contains five known objects of intermediate size classified as dwarf planets and a very large number of much smaller objects collectively called small bodies.

- The small bodies, roughly in order of decreasing size, are the asteroids, or minor planets; comets, including Kuiper belt, Centaur, and Oort cloud objects; meteoroids; and interplanetary dust particles.

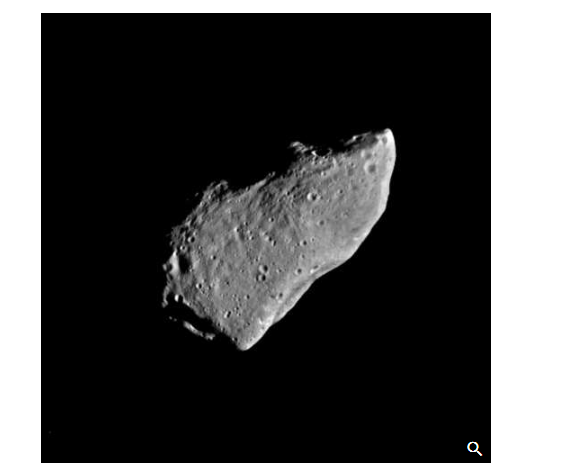

- Because of their starlike appearance when discovered, the largest of these bodies were termed asteroids, and that name is widely used, but, now that the rocky nature of these bodies is understood, their more descriptive name is minor planets.

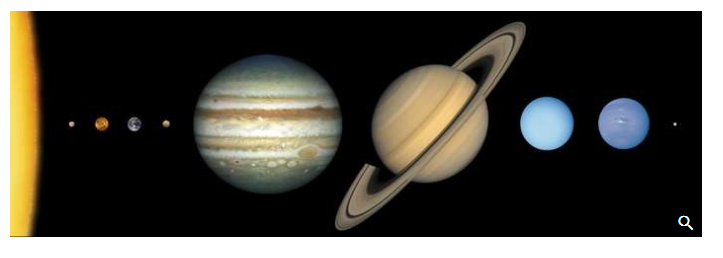

- The four inner, terrestrial planets—Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars—along with the Moon have average densities in the range of 3.9–5.5 grams per cubic cm, setting them apart from the four outer, giant planets—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—whose densities are all close to 1 gram per cubic cm, the density of water.

- The compositions of these two groups of planets must therefore be significantly different. This dissimilarity is thought to be attributable to conditions that prevailed during the early development of the solar system (see below Theories of origin).

- Planetary temperatures now range from around 170 °C (330 °F, 440 K) on Mercury’s surface through the typical 15 °C (60 °F, 290 K) on Earth to −135 °C (−210 °F, 140 K) on Jupiter near its cloud tops and down to −210 °C (−350 °F, 60 K) near Neptune’s cloud tops.

- These are average temperatures; large variations exist between dayside and nightside for planets closest to the Sun, except for Venus with its thick atmosphere.

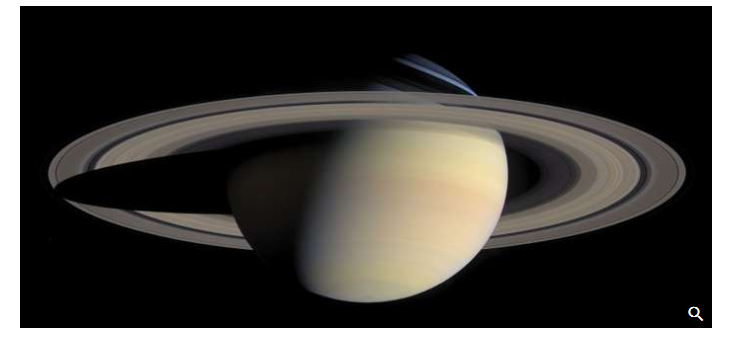

(Saturn and its spectacular rings, in a natural-colour composite of 126 images taken by the Cassini spacecraft on October 6, 2004. The view is directed toward Saturn's southern hemisphere, which is tipped toward the Sun. Shadows cast by the rings are visible against the bluish northern hemisphere, while the planet's shadow is projected on the rings to the left.)

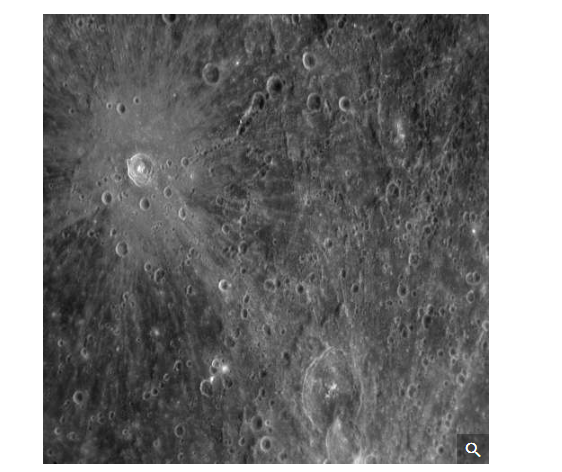

- The surfaces of the terrestrial planets and many satellites show extensive cratering, produced by high-speed impacts (see meteorite crater).

- On Earth, with its large quantities of water and an active atmosphere, many of these cosmic footprints have eroded, but remnants of very large craters can be seen in aerial and spacecraft photographs of the terrestrial surface.

- On Mercury, Mars, and the Moon, the absence of water and any significant atmosphere has left the craters unchanged for billions of years, apart from disturbances produced by infrequent later impacts.

- Volcanic activity has been an important force in the shaping of the surfaces of the Moon and the terrestrial planets.

- Seismic activity on the Moon has been monitored by means of seismometers left on its surface by Apollo astronauts and by Lunokhod robotic rovers.

- Cratering on the largest scale seems to have ceased about three billion years ago, although on the Moon there is clear evidence for a continued cosmic drizzle of small particles, with the larger objects churning (“gardening”) the lunar surface and the smallest producing microscopic impact pits in crystals in the lunar rocks.

Mercury

Meteorite crater surrounded by rays of ejected material on Mercury, in a photograph taken by the Messenger probe, January 14, 2008. A chain of craters crosses the centre of the rayed crater.

- All of the planets apart from the two closest to the Sun (Mercury and Venus) have natural satellites (moons) that are very diverse in appearance, size, and structure, as revealed in close-up observations from long-range space probes.

- The four outer dwarf planets have moons; Pluto has at least five moons, including one, Charon, fully half the size of Pluto itself.

- Over 200 asteroids and 80 Kuiper belt objects also have moons. Four planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune), one dwarf planet (Haumea), and one Centaur object (Chariklo) have rings, disklike systems of small rocks and particles that orbit their parent bodies.

Lunar exploration

- During the U.S. Apollo missions a total weight of 381.7 kg (841.5 pounds) of lunar material was collected; an additional 300 grams (0.66 pounds) was brought back by unmanned Soviet Luna vehicles.

- About 15 percent of the Apollo samples have been distributed for analysis, with the remainder stored at the NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas.

- The opportunity to employ a wide range of laboratory techniques on these lunar samples has revolutionized planetary science.

- The results of the analyses have enabled investigators to determine the composition and age of the lunar surface. Seismic observations have made it possible to probe the lunar interior.

- In addition, retroreflectors left on the Moon’s surface by Apollo astronauts have allowed high-power laser beams to be sent from Earth to the Moon and back, permitting scientists to monitor the Earth-Moon distance to an accuracy of a few centimetres.

- This experiment, which has provided data used in calculations of the dynamics of the Earth-Moon system, has shown that the separation of the two bodies is increasing by 4.4 cm (1.7 inches) each year. (For additional information on lunar studies, see Moon.)

Planetary studies

- Mercury is too hot to retain an atmosphere, but Venus’s brilliant white appearance is the result of its being completely enveloped in thick clouds of carbon dioxide, impenetrable at visible wavelengths.

- Below the upper clouds, Venus has a hostile atmosphere containing clouds of sulfuric acid droplets.

- The cloud cover shields the planet’s surface from direct sunlight, but the energy that does filter through warms the surface, which then radiates at infrared wavelengths.

- The long-wavelength infrared radiation is trapped by the dense clouds such that an efficient greenhouse effect keeps the surface temperature near 465 °C (870 °F, 740 K).

- Radar, which can penetrate the thick Venusian clouds, has been used to map the planet’s surface. In contrast, the atmosphere of Mars is very thin and is composed mostly of carbon dioxide (95 percent), with very little water vapour; the planet’s surface pressure is only about 0.006 that of Earth.

- The outer planets have atmospheres composed largely of light gases, mainly hydrogen and helium.

- Each planet rotates on its axis, and nearly all of them rotate in the same direction—counterclockwise as viewed from above the ecliptic.

- The two exceptions are Venus, which rotates in the clockwise direction beneath its cloud cover, and Uranus, which has its rotation axis very nearly in the plane of the ecliptic.

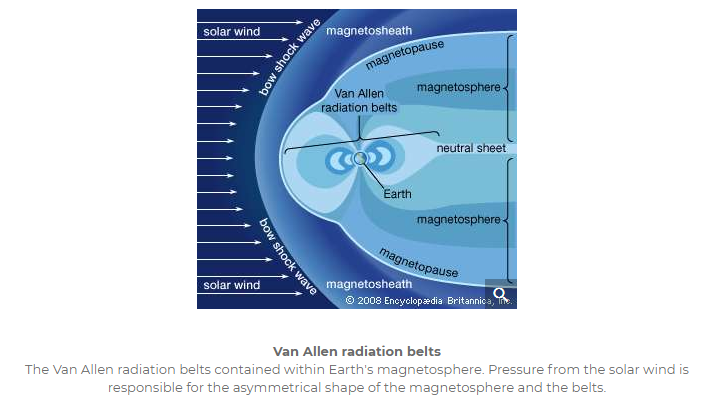

- Some of the planets have magnetic fields. Earth’s field extends outward until it is disturbed by the solar wind—an outward flow of protons and electrons from the Sun—which carries a magnetic field along with it.

- Through processes not yet fully understood, particles from the solar wind and galactic cosmic rays (high-speed particles from outside the solar system) populate two doughnut-shaped regions called the Van Allen radiation belts.

- The inner belt extends from about 1,000 to 5,000 km (600 to 3,000 miles) above Earth’s surface, and the outer from roughly 15,000 to 25,000 km (9,300 to 15,500 miles).

- In these belts, trapped particles spiral along paths that take them around Earth while bouncing back and forth between the Northern and Southern hemispheres, with their orbits controlled by Earth’s magnetic field.

- During periods of increased solar activity, these regions of trapped particles are disturbed, and some of the particles move down into Earth’s atmosphere, where they collide with atoms and molecules to produce auroras.

- Jupiter has a magnetic field far stronger than Earth’s and many more trapped electrons, whose synchrotron radiation (electromagnetic radiation emitted by high-speed charged particles that are forced to move in curved paths, as under the influence of a magnetic field) is detectable from Earth.

- Bursts of increased radio emission are correlated with the position of Io, the innermost of the four Galilean moons of Jupiter.

- Saturn has a magnetic field that is much weaker than Jupiter’s, but it too has a region of trapped particles.

- Mercury has a weak magnetic field that is only about 1 percent as strong as Earth’s and shows no evidence of trapped particles.

- Uranus and Neptune have fields that are less than one-tenth the strength of Saturn’s and appear much more complex than that of Earth. No field has been detected around Venus or Mars.

Investigations of the smaller bodies

- More than 500,000 asteroids with well-established orbits are known, and thousands of additional objects are discovered each year.

- Hundreds of thousands more have been seen, but their orbits have not been as well determined.

- It is estimated that several million asteroids exist, but most are small, and their combined mass is estimated to be less than a thousandth that of Earth.

- Most of the asteroids have orbits close to the ecliptic and move in the asteroid belt, between 2.3 and 3.3 AU from the Sun. Because some asteroids travel in orbits that can bring them close to Earth, there is a possibility of a collision that could have devastating results (see Earth impact hazard).

Comets

- Comets are considered to come from a vast reservoir, the Oort cloud, orbiting the Sun at distances of 20,000–50,000 AU or more and containing trillions of icy objects—latent comet nuclei—with the potential to become active comets.

- Many comets have been observed over the centuries. Most make only a single pass through the inner solar system, but some are deflected by Jupiter or Saturn into orbits that allow them to return at predictable times.

- Halley’s Comet is the best known of these periodic comets; its next return into the inner solar system is predicted for 2061.

- Many short-period comets are thought to come from the Kuiper belt, a region lying mainly between 30 AU and 50 AU from the Sun—beyond Neptune’s orbit but including part of Pluto’s—and housing perhaps hundreds of millions of comet nuclei.

- Very few comet masses have been well determined, but most are probably less than 1018 grams, one-billionth the mass of Earth.

- Since the 1990s more than a thousand comet nuclei in the Kuiper belt have been observed with large telescopes; a few are about half the size of Pluto, and Pluto is the largest Kuiper belt object.

- Pluto’s orbital and physical characteristics had long caused it to be regarded as an anomaly among the planets.

- However, after the discovery of numerous other Pluto-like objects beyond Neptune, Pluto was seen to be no longer unique in its “neighbourhood” but rather a giant member of the local population.

- Consequently, in 2006 astronomers at the general assembly of the International Astronomical Union elected to create the new category of dwarf planets for objects with such qualifications.

- Pluto, Eris, and Ceres, the latter being the largest member of the asteroid belt, were given this distinction. Two other Kuiper belt objects, Makemake and Haumea, were also designated as dwarf planets.

- Smaller than the observed asteroids and comets are the meteoroids, lumps of stony or metallic material believed to be mostly fragments of asteroids. Meteoroids vary from small rocks to boulders weighing a ton or more.

- A relative few have orbits that bring them into Earth’s atmosphere and down to the surface as meteorites. Most meteorites that have been collected on Earth are probably from asteroids. A few have been identified as being from the Moon, Mars, or the asteroid Vesta.

Meteorites

- Meteorites are classified into three broad groups: stony (chondrites and achondrites; about 94 percent), iron (5 percent), and stony-iron (1 percent).

- Most meteoroids that enter the atmosphere heat up sufficiently to glow and appear as meteors, and the great majority of these vaporize completely or break up before they reach the surface.

- Many, perhaps most, meteors occur in showers (see meteor shower) and follow orbits that seem to be identical with those of certain comets, thus pointing to a cometary origin.

- For example, each May, when Earth crosses the orbit of Halley’s Comet, the Eta Aquarid meteor shower occurs.

- Micrometeorites (interplanetary dust particles), the smallest meteoroidal particles, can be detected from Earth-orbiting satellites or collected by specially equipped aircraft flying in the stratosphere and returned for laboratory inspection.

- Since the late 1960s numerous meteorites have been found in the Antarctic on the surface of stranded ice flows (see Antarctic meteorites).

- Some meteorites contain microscopic crystals whose isotopic proportions are unique and appear to be dust grains that formed in the atmospheres of different stars.

Theories of origin

- The origin of Earth, the Moon, and the solar system as a whole is a problem that has not yet been settled in detail. The Sun probably formed by condensation of the central region of a large cloud of gas and dust, with the planets and other bodies of the solar system forming soon after, their composition strongly influenced by the temperature and pressure gradients in the evolving solar nebula. Less-volatile materials could condense into solids relatively close to the Sun to form the terrestrial planets. The abundant, volatile lighter elements could condense only at much greater distances to form the giant gas planets.

- In the 1990s astronomers confirmed that other stars have one or more planets revolving around them. Studies of these planetary systems have both supported and challenged astronomers’ theoretical models of how Earth’s solar system formed. Unlike the solar system, many extrasolar planetary systems have large gas giants like Jupiter orbiting very close to their stars, and in some cases these “hot Jupiters” are closer to their star than Mercury is to the Sun.

- That so many gas giants, which form in the outer regions of their system, end up so close to their stars suggests that gas giants migrate and that such migration may have happened in the solar system’s history. According to the Grand Tack hypothesis, Jupiter may have done so within a few million years of the solar system’s formation. In this scenario, Jupiter is the first giant planet to form, at about 3 AU from the Sun. Drag from the protoplanetary disk causes it to fall inward to about 1.5 AU. However, by this time, Saturn begins to form at about 3 AU and captures Jupiter in a 3:2 resonance. (That is, for every three revolutions Jupiter makes, Saturn makes two.) The two planets migrate outward and clear away any material that would have gone to making Mars bigger. Mars should be bigger than Venus or Earth, but it is only half their size. The Grand Tack, in which Jupiter moves inward and then outward, explains Mars’s small size.

- About 500 million years after the Grand Tack, according to the Nice Model (named after the French city where it was first proposed), after the four giant planets—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—formed, they orbited 5–17 AU from the Sun. These planets were in a disk of smaller bodies called planetesimals and in orbital resonances with each other. About four billion years ago, gravitational interactions with the planetesimals increased the eccentricity of the planets’ orbits, driving them out of resonance. Saturn, Uranus and Neptune migrated outward, and Jupiter migrated slightly inward. (Uranus and Neptune may even have switched places.) This migration scattered the disk, causing the Late Heavy Bombardment. The final remnant of the disk became the Kuiper belt.

- The origin of the planetary satellites is not entirely settled. As to the origin of the Moon, the opinion of astronomers long oscillated between theories that saw its origin and condensation as simultaneous with the formation of Earth and those that posited a separate origin for the Moon and its later capture by Earth’s gravitational field. Similarities and differences in abundances of the chemical elements and their isotopes on Earth and the Moon challenged each group of theories. Finally, in the 1980s a model emerged that gained the support of most lunar scientists—that of a large impact on Earth and the expulsion of material that subsequently formed the Moon. (See Moon: Origin and evolution.) For the outer planets, with their multiple satellites, many very small and quite unlike one another, the picture is less clear. Some of these moons have relatively smooth icy surfaces, whereas others are heavily cratered; at least one, Jupiter’s Io, is volcanic. Some of the moons may have formed along with their parent planets, and others may have formed elsewhere and been captured.

Study of extrasolar planetary systems

- The first extrasolar planets were discovered in 1992, and more than 4,100 such planets are now known. Over 600 of these systems have more than one planet. Because planets are much fainter than their stars, fewer than 100 have been imaged directly. Most extrasolar planets have been found through their transit, the small dimming of a star’s light when a planet passes in front of it. Many of these planets are unlike those of the solar system. Hot Jupiters are large gas giants that orbit very close to their star.

- A primary goal of extrasolar planet research has been finding another planet that could support life. A useful guide for finding a life-supporting planet has been the concept of a habitable zone, the distance from a star where liquid water could survive on a planet’s surface. About 20 planets have been found that are roughly Earth-sized and orbit in a habitable zone.

Star formation and evolution

- The range of physically allowable masses for stars is very narrow. If the star’s mass is too small, the central temperature will be too low to sustain fusion reactions. The theoretical minimum stellar mass is about 0.08 solar mass. An upper theoretical bound called the Eddington limit, of several hundred solar masses, has been suggested, but this value is not firmly defined. Stars as massive as this will have luminosities about one million times greater than that of the Sun.

- A general model of star formation and evolution has been developed, and the major features seem to be established. A large cloud of gas and dust can contract under its own gravitational attraction if its temperature is sufficiently low. As gravitational energy is released, the contracting central material heats up until a point is reached at which the outward radiation pressure balances the inward gravitational pressure, and contraction ceases. Fusion reactions take over as the star’s primary source of energy, and the star is then on the main sequence. The time to pass through these formative stages and onto the main sequence is less than 100 million years for a star with as much mass as the Sun. It takes longer for less massive stars and a much shorter time for those much more massive.

- Once a star has reached its main-sequence stage, it evolves relatively slowly, fusing hydrogen nuclei in its core to form helium nuclei. Continued fusion not only releases the energy that is radiated but also results in nucleosynthesis, the production of heavier nuclei.

- Stellar evolution has of necessity been followed through computer modeling, because the timescales for most stages are generally too extended for measurable changes to be observed, even over a period of many years. One exception is the supernova, the violently explosive finale of certain stars. Different types of supernovas can be distinguished by their spectral lines and by changes in luminosity during and after the outburst. In Type Ia, a white dwarf star attracts matter from a nearby companion; when the white dwarf’s mass exceeds about 1.4 solar masses, the star implodes and is completely destroyed. Type II supernovas are not as luminous as Type Ia and are the final evolutionary stage of stars more massive than about eight solar masses. Type Ib and Ic supernovas are like Type II in that they are from the collapse of a massive star, but they do not retain their hydrogen envelope.

- The nature of the final products of stellar evolution depends on stellar mass. Some stars pass through an unstable stage in which their dimensions, temperature, and luminosity change cyclically over periods of hours or days. These so-called Cepheid variables serve as standard candles for distance measurements (see above Determining astronomical distances). Some stars blow off their outer layers to produce planetary nebulas. The expanding material can be seen glowing in a thin shell as it disperses into the interstellar medium while the remnant core, initially with a surface temperature as high as 100,000 K (180,000 °F), cools to become a white dwarf. The maximum stellar mass that can exist as a white dwarf is about 1.4 solar masses and is known as the Chandrasekhar limit. More-massive stars may end up as either neutron stars or black holes.

- The average density of a white dwarf is calculated to exceed one million grams per cubic cm. Further compression is limited by a quantum condition called degeneracy (see degenerate gas), in which only certain energies are allowed for the electrons in the star’s interior. Under sufficiently great pressure, the electrons are forced to combine with protons to form neutrons. The resulting neutron star will have a density in the range of 1014–1015 grams per cubic cm, comparable to the density within atomic nuclei. The behaviour of large masses having nuclear densities is not yet sufficiently understood to be able to set a limit on the maximum size of a neutron star, but it is thought to be less than three solar masses.

- Still more-massive remnants of stellar evolution would have smaller dimensions and would be even denser that neutron stars. Such remnants are conceived to be black holes, objects so compact that no radiation can escape from within a characteristic distance called the Schwarzschild radius. This critical dimension is defined by Rs = 2GM/c2. (Rs is the Schwarzschild radius, G is the gravitational constant, M is the object’s mass, and c is the speed of light.) For an object of three solar masses, the Schwarzschild radius would be about three kilometres. Radiation emitted from beyond the Schwarzschild radius can still escape and be detected.

- Although no light can be detected coming from within a black hole, the presence of a black hole may be manifestedthrough the effects of its gravitational field, as, for example, in a binary star If a black hole is paired with a normal visible star, it may pull matter from its companion toward itself. This matter is accelerated as it approaches the black hole and becomes so intensely heated that it radiates large amounts of X-rays from the periphery of the black hole before reaching the Schwarzschild radius. Some candidates for stellar black holes have been found—e.g., the X-ray source Cygnus X-1. Each of them has an estimated mass clearly exceeding that allowable for a neutron star, a factor crucial in the identification of possible black holes. Supermassive black holes that do not originate as individual stars exist at the centre of active galaxies (see below Study of other galaxies and related phenomena). One such black hole, that at the center of the galaxy M87, has a mass 6.5 billion times that of the Sun and has been directly observed.

- Whereas the existence of stellar black holes has been strongly indicated, the existence of neutron stars was confirmed in 1968 when they were identified with the then newly discovered pulsars, objects characterized by the emission of radiation at short and extremely regular intervals, generally between 1 and 1,000 pulses per second and stable to better than a part per billion. Pulsars are considered to be rotating neutron stars, remnants of some supernovas.

No comments:

Post a Comment